Learning Pilotage Can Save Your Life

You can navigate without the GPS—the magenta line should come later.

Man-made objects, such as bridges, large buildings or clusters of buildings, stadiums, race tracks and airports all make good visual checkpoints. [Credit: Wolf Godlewski]

Recently a friend shared a newspaper article regarding a recent speed record set by the pilot of a single-engine piston aircraft on a flight between Chicago and Omaha, Nebraska. What caught our attention was the author's note that the pilot "navigated only by sight, without using instruments, following maps and ground landmarks.’’ This practice is known as pilotage, something VFR pilots have been doing since the beginning days of aviation.

I was confused as to why the author would mention the lack of GPS use—then it occurred to me that we live in the age of the GPS. It is on our phones, in our cars—and many of our airplanes—so choosing to navigate by pilotage may seem to some pilots as quaint as listening to a vinyl record.

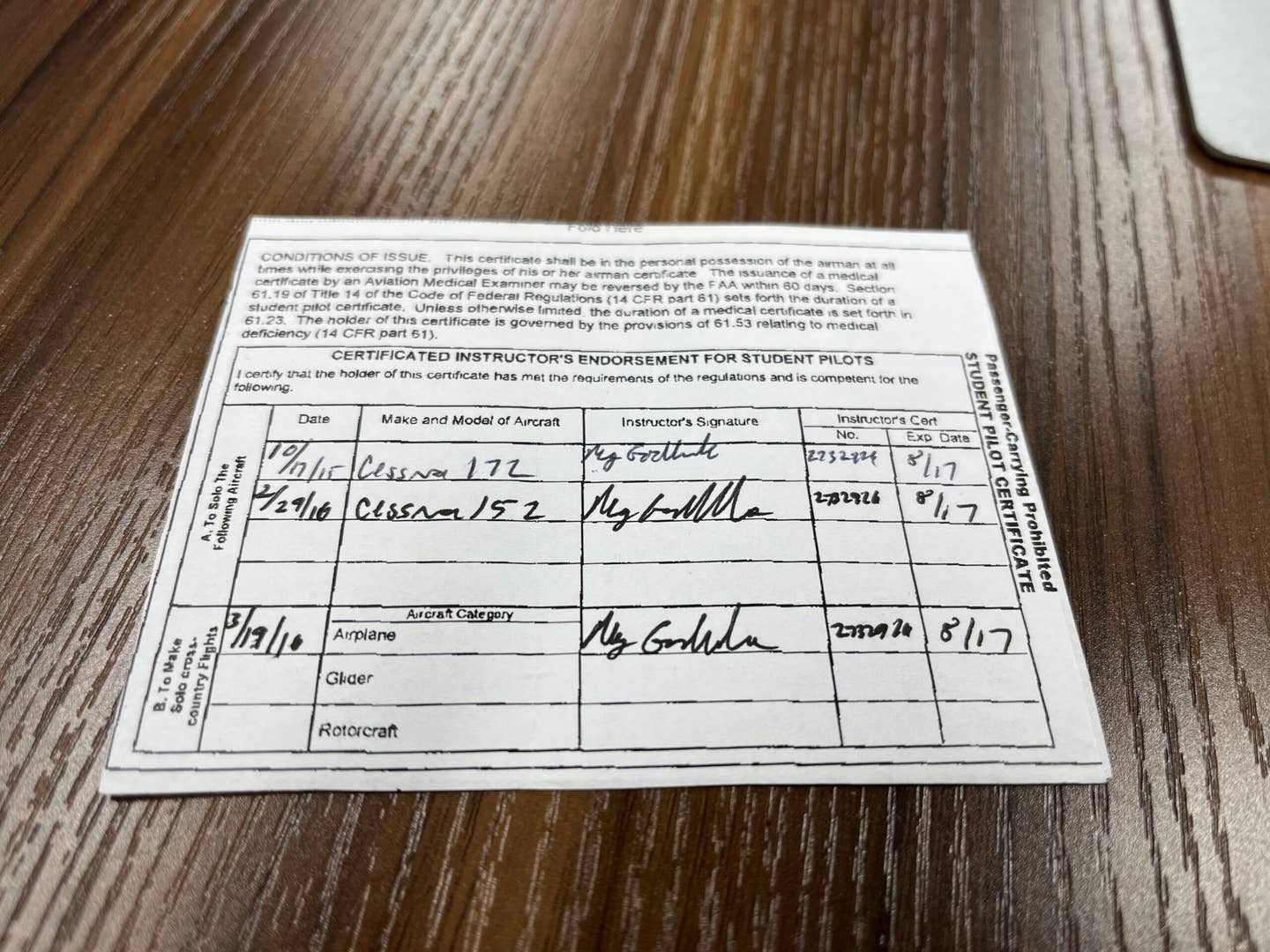

Pilotage Should Be Learned Early

Pilotage is the first form of navigation we learn. You were probably using a ground-based version of it before you could read, as you navigated your way around the neighborhood by landmarks, such as the park, the railroad tracks, the big, red two-story house on the corner, etc.

During your flight lessons, your CFI will point out objects on the ground asking if you see them. This serves two purposes: it is a realistic distraction—as you learn to divide your attention between flying the airplane and looking for landmarks—and you will learn what makes a good landmark to use as a checkpoint for navigation. If you can see the object from a few thousand feet in the air, it's a good checkpoint.

You will learn to use these checkpoints to get from the airport to the practice area and back again. Please remember that just because you can see something well from the ground—like a billboard along the highway—that doesn't necessarily mean it will be a good checkpoint in the air.

Man-made objects, such as bridges, large buildings or clusters of buildings (think of a tech or college campus), and stadiums, race tracks and airports make good checkpoints.

Natural checkpoints also make good markers, such as shorelines, distinctive rivers, lakes, and mountains—I am talking about distinctive rocks like Mount Rainier, Mount Hood, or Camelback Mountain—you want the ones that stick out like a frog in a punchbowl.

Pilotage is a combination of these landmarks and following along on the map. The technical term for this is digital-ocular navigation because while looking out the window you have one finger on the map. When you do your planning, aim to have the checkpoints pass off the left or right side of the aircraft if possible because if the path takes you directly over the object you can miss it.

What About Water Towers?

You've probably heard stories about the early barnstormers who flew their WWI surplus aircraft town to town using pilotage. Sometimes they swooped down low to see the names of the towns painted on water towers. The water tower verification was necessary because many of the towns looked alike from the air—they all were laid out by railroad companies in the 1800s and there wasn't a lot of deviation. The train station and a horse-racing track were on one side, with houses, schools, and churches on the other.

There are even stories of some pilots who flew so low they could see the name of the train station on the building. This is not a good idea these days as the FAA takes a pretty dim view of low flying aircraft, and you don't want to be the guy captured on a doorbell cam who ends up on YouTube for allegedly buzzing someone or something.

Airports are easier to locate from the air as many have the name of the airport painted on the taxiway. This process is called airmarking and it is often done by the Ninety-Nines, the international organization of women pilots. The airport sponsor often supplies the paint and painting supplies and the women supply the labor.

GPS Has Become a Habit

Some pilots are so accustomed to using GPS that they automatically reach for it when instructed to proceed to someplace even in VFR conditions. There are times when flying ‘direct to’ is not a good idea, such as when flying in the mountains.

During a simulator session at the Pilot Proficiency Center at EAA AirVenture, I witnessed an ATP-certificated pilot who, when instructed to return to the mountain airstrip she'd just departed from five minutes earlier, immediately entered the identifier in the GPS and hit the "direct" button. She turned to the heading—and put the "aircraft" on a collision course with a mountain. The instructor pointed this out, suggesting that pilotage was the recommended course of action, reminding the pilot of the burn scar on the hillside and the hairpin turn in the road they had followed away from the airport and so cleverly depicted in the Redbird computer simulation.

The use of GPS is such a habit, a crutch if you will, that some pilots are anxious at the idea of flying without it. This often manifests in low-time pilots, especially learners when their instructor has pushed the use of GPS over pilotage.

Some learners interpret this to mean that GPS is a requirement for VFR flight. This is not accurate, GPS is a "nice to have" in the aircraft.

A colleague of mine discovered a learner at his school was under the impression that GPS was required when he was moved into a non-GPS aircraft because of a maintenance issue and promptly canceled the cross-country flight because he thought GPS was required for the flight.

Other times, it comes down to the learner’s lack of confidence in their navigation skills. This makes them reluctant to attempt a solo cross-country without a GPS on board.

The Fear of Getting Lost

Getting lost is a common fear. It often begins in childhood—all it takes is losing your direction in a cornfield when the stalks were taller than you were or getting separated from your parents in a shopping mall—and that fear is ingrained.

Thankfully, these experiences are often tempered by the "what to do if you get lost again" discussion, and we are given instructions to if it happens again with the hopes we never have to use them.

Full disclosure: My childhood "lost" experience was a bit backwards—before I was allowed to venture out on camping trips with my scout troop Dad took me on hikes in the hills behind our home and taught me wilderness survival skills. While other little girls were learning to play jacks and hosting teddy bear tea parties, I was learning to build shelters out of brush and how to mark a trail by tying plants in knots and stacking sticks and rocks. Dad wanted me to be prepared, just as your flight instructor wants you to be prepared—which is why we teach the five Cs of being lost.

The Five Cs

When you realize that you are lost, or think you might be lost, you need to stay calm—sometimes easier said than done—but if you run through the five Cs it helps:

Climb

If able, to get a better view of the terrain. Don't go into a cloud, but even climbing a few hundred feet can dramatically improve visibility.

Circle

Note the heading you are on, then enter a half-standard rate turn holding your altitude for a 360 degree turn to the left using rudder only as you look outside for landmarks and compare them to what you see on the sectional.

Conserve (reduce power to save fuel)

If you are flying at 65 percent power, reduce to 55 percent. Don't stall the aircraft, but don't race around like beheaded poultry either.

Confess

Let ATC know you are lost. If you use flight following, they will likely figure it out before you do—they may ask you to confirm your destination, then advise a heading change. If you are not using flight following, find the local approach frequency on the sectional and notify them of the situation.

If you feel your life is in danger, use the emergency frequency or 121.5. Explain you are a student pilot and lost.

Comply

If ATC tells you to turn to a heading of 160, turn to that heading. They may ask you to put in a discreet squawk code—do that too.

Understand that everyone feels a little anxious the first time they leave the pattern by themselves, but with repetition comes confidence.

One of the most experienced pilots I know had this fear when she was a learner in a Piper J-3 Cub some 20-plus years ago. This made her reluctant to do her first solo cross-country flight, as navigation was done by looking out the window, with a magnetic compass, and an analog watch.

Her instructor helped her overcome her fears by easing her away from the airport—10 miles out and back, 20 miles out and back, 30 miles out and so forth, building her navigational skills and confidence until she felt ready to make her first solo cross-country flight.

The funny thing was, her instructor didn't tell her this was being done to get over her fear of getting lost—going farther from the airport was just a fun thing they were doing—and learning took place.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox